As Bhutan continued to meet the thresholds in the same two criteria, the CDP during its March 2018 Triennial Review recommended for graduation to the ECOSOC. Further, the independent vulnerability profile reports of UNCTAD and ex-ante impact assessment of UNDESA had positive assessments in terms of Bhutan’s graduation from LDC.

With the standard transition period, Bhutan would have graduated in 2021. However, the Government conveyed to the CDP the need for a longer transition period of 5 years coinciding with the 12th Five Year Plan period.

On the basis of the performance of LDC criteria and assessments by UNCTAD and UNDESA, General Assembly resolution A/RES/73/133 adopted on 13 December 2018, decided that Bhutan will graduate five years after the adoption of the resolution, i.e. on 13 December 2023.

Even in 2021 triennial review, Bhutan fulfilled all three criteria after the revision of EVI criteria and reaffirmed CDP’s recommendation of Bhutan’s graduation.

Are we ready?

While the UN development indicators enable Bhutan to graduate by 2023, the question is; are we ready and prepared to graduate? This can be answered by critically reviewing Bhutan's achievement in respective criterion for LDC graduation in relation to existing developmental challenges. I will leave out the implications of graduation for there are already several publications.

Bhutan’s LDC Performance

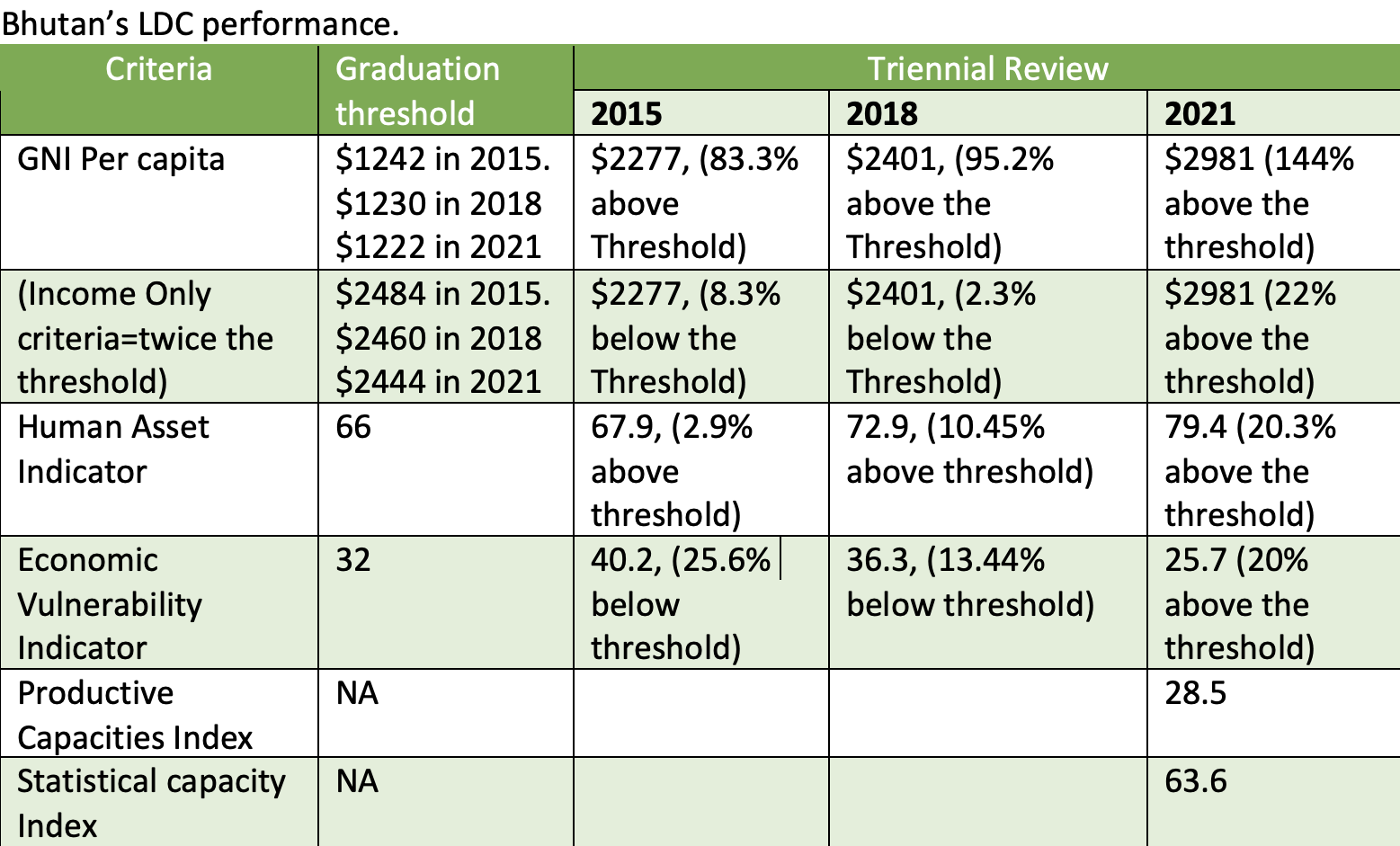

Table: Bhutan’s performance in the CDP Triennial Review

Source: Committee for Development Policy, United NationsGNI Per capita;

1.1. Gross National Income (GNI) Per capita.

While the GNI indicator performance records a tremendous success, the significant contributions are from resource intensive and climate sensitive sectors such as hydropower and tourism (biodiversity) with limited degree of manufacturing. The private sectors are yet to unleash their full potential and tax revenues are very modest in it’s contribution to GDP. Further, the impact of covid 19 pandemic led to a decrease of GDP and GNI to USD 2325 and 2306 respectively in 2020. The GDP growth rate nosedived to -10 in the same year. It was estimated to have an economic loss of Nu.10 billion in the process of containing covid 19 pandemic. Thus, while the rapid rise of per capita income signals a quick prosperity it hides the structural impediments to economic diversification.

The growth in the GDP and GNI also did not have commensurate job creation as the unemployment rates are high amongst the undergraduates. The hydropower and industry have a disproportionate contribution to jobs and GDP. In addition, the income disparities between rural- urban areas remain a developmental challenge to address and widened further by the covid 19 impacts in 2020 through lay-offs, furloughs, leave without pay or reduced wages and inflated prices of basic goods.

1.2 Human Asset Index (HAI)

As far as HAI is concerned, Bhutan has done considerably well on educational sub-indicators which captures the gross secondary enrollment, gender parity index in secondary enrolment and adult literacy. However, the learning outcomes and the quality of the education have come under public scrutiny that it is not up to the standard both nationally and internationally. Further, the access to Early Childhood care and development (ECCD) facilities are limited and tertiary education is grappling with increasing demand of students, limited resources and rapidly changing skills requirements. The absorption of graduates and educated youths into the civil service and corporation is minimal and private sectors are not able to employ due to mismatch of skills and lack of experiences. Youths face difficulty in finding jobs and many are looking to go abroad for income opportunities but by undertaking blue collar jobs such as cleaner and elderly caregivers. Such aforementioned ground realities are camouflaged in the HAI parameters and graduation from LDC will have huge implications in human resource development.

With regard to health indicators, the criteria covers prevalence of stunting, under five mortality rate and maternal mortality rate. As of 2021, the NSB recorded under five mortality at 34.1 while the stunting value at 23 and maternal mortality value at 185. The 2015 national nutritional survey reported the prevalence of stunting among children under five years of age at 21.2%. The report also recorded the health concern of prevalence of 43.8% and almost 40% of anemia in women and adolescent girls respectively.

Further, non-communicable disease has become the main disease burden and cause of premature death in the country. NCD is reported to be the main cause of more than 50% death in the country. The country's policy of free public healthcare is known to be a substantial financial liability and therefore, sustainability remains an issue to address. Covid 19 pandemic also indicated the need for Bhutan to develop a robust mechanism to respond to health needs during emergencies and aftermath of natural disasters. In the immediate term, Bhutan needs to address the human resource shortage in health sectors.

In general, while the education and health indicators confirm the development progress, there is no commensurate success in poverty rate reduction. The recent NSB report recorded a spike in poverty rate to 12.4% from 8.2% in 2017. This translates into 80614 people living under the poverty line with less than Nu.6204 people per month.

1.3) Economic and Environmental Vulnerability Index

The EVI is composed of indicators of share of agriculture, hunting, forestry and fishing in GDP, remoteness and landlockedness, merchandise export concentration, instability of exports of goods and services, share of population in low elevated coastal zones, share of the population living in drylands, instability of agricultural production, and victims of disasters.

Bhutan fulfilled the vulnerability index for the first time in the 2021 triennial review after the revision of vulnerability criteria by adding environmental dimension. In a recent review, Bhutan’s share value of agriculture, hunting, forestry and fishing stands at 16.2. The value for remoteness and landlockedness stands at 51.2 and merchandise export concentration at 0. 37 while the instability of exports of goods and services at 10. The value of instability of agricultural production is at 7.4 and victims of disasters at 0.15.

While this remains an achievement for Bhutan, other economic challenges such as unstable macroeconomic environment, growing debt burden, lack of technology and human capital, a lack of productive capacities, an insufficiently diversified economic base and export basket that inhibits trade expansion, and marked vulnerability to natural disasters will have significant bearings on building resilience and more so after the graduation.

While the agriculture sector remains to be the largest employer at 57.2%, there is not much of a commensurate GDP contribution (16.5%). At the same time, the limited shift of workforce from agriculture to manufacturing distinguishes the economy as largely agrarian and requires some further structural economic transformation. The sector is prone to Climate change related disasters and human- wildlife conflict.

On the flip side, the share of manufacturing remained very small at just 11 percent with most MSMEs engaged in the production of low value-added products. The private sector is still at a nascent stage and our industrial production is plagued with severe supply chain issues, rising input and transaction costs and inefficient market linkages despite the overall improvement in infrastructure such as roads, telecommunication, ICT and transport. According to the 2018 World Bank Logistics Performance Index (LPI), Bhutan has one of the weakest logistics performance (second to Afghanistan)scoring particularly low on the quality of trade and transport related infrastructure. The FDI inflows to Bhutan are considered to be lower than FDI flows to other LDCs in the South Asia region.

Similarly, the country’s highest revenue generating sector of hydropower is unable to provide enough employment opportunities for the domestic workforce. Our heavy reliance on the sector for growth and export leads to macroeconomic uncertainties and vulnerabilities. In light of the increased climate-change, adverse weather events could negatively affect electricity generation from existing plants and, in turn, affect energy-intensive industries. In addition, hydropower is plagued with delays in construction, enormous cost escalation, and causing factors for mounting public debts.

On the trading front, Bhutan faces numerous exogenous and endogenous challenges to trade, including the heavy reliance on the Indian market, changing global trading system, restrictive customs procedures, supply constraints and inadequacies of trade‐related infrastructure, and undiversified export basket and export markets. Such weak productive capacities and limited export diversification have resulted in high import content in domestic consumption and production leading to trade and account deficit. Further, owing to limited access to regional and international markets by Bhutan’s producers, we have not been able to increase trade value of goods and services significantly as compared to other LDCs in the region such as Nepal.

Environmentally, Bhutan’s mountainous and fragile topography is susceptible to natural disasters such as Glacial lake outburst floods, persistent landslides, frequent earthquakes, floods, forest fires, and windstorms. In addition, the country lacks the financial resources and technical expertise to adequately manage frequent disasters.